Background

Wigs are worn for either prosthetic, cosmetic, or convenience reasons. People who have lost all or part of their own hair due to illness or natural baldness can disguise the condition. For strictly cosmetic reasons (or perhaps to alter their appearance), people might wear a wig to quickly achieve a longer or fuller hairstyle or a different color. In an article in Vogue magazine, the wife of a prominent politician was described as using a wardrobe of wigs to avoid $8,400 and 160 or more hours spent with professional hairdressers each year, in addition to the complicated task of finding appropriate hair care while traveling.

History

Based on an ivory carving of a woman's head found in southwestern France, anthropologists speculate that wigs may have been used as long as 100,000 years ago. Wigs were quite popular among ancient Egyptians, who cut their hair short or shaved their heads in the interests of cleanliness and comfort (i.e., relief from the desert heat). While the poor wore felt caps to protect their heads from the sun, those who could afford them wore wigs of human hair, sheep's wool, or palm-leaf fiber mounted on a porous fabric. An Egyptian clay figure that dates to about 2500 B.C. wears a removable wig of black clay. The British Museum holds a beautifully made wig at least 3,000 years old that was found in the Temple of Isis at Thebes; its hundreds of tiny curls still retain their carefully arranged shape.

Wigs were popular in ancient Greece, both for personal use and in the theater (the color and style of wigs disclosed the nature of individual characters). In Imperial Rome, fashionable women wore blond or red-haired wigs made from the heads of Germanic captives, and Caesar used a wig and a laurel wreath to hide his baldness. Both Hannibal and Nero wore wigs as disguises. A portrait bust of Plautilla (ca. 210 A.D. ) was made without hair so wigs of current fashion could always adorn this image of Emperor Caracalla's wife.

During the reign of Stephen in the middle third of the twelfth century, wigs were introduced in England; they became increasingly common, and women began to wear them in the late sixteenth century. Italian wigs of that time were made of either human hair or silk thread. In 1630, embarrassed by his baldness, Louis XIII began wearing a wig made of hair sewn onto a linen foundation. Wigs became fashionable, increasing in popularity during the reign of Louis XIV, who not only wore them to hide his baldness but also to make himself seem taller by means of towering hair. During the Plague of 1665, hair was in such short supply that there were persistent rumors of the hair of disease victims being used to manufacture wigs. This shortage of hair was partially remedied by using wool or the hair of goats or horses to make lower grades of wigs (in fact, horsehair proved useful since it retained curls effectively). For several decades around 1700, men were warned to be watchful as they walked the streets of London, lest their wigs be snatched right off their heads by daring thieves.

The enormous popularity of wigs in England declined markedly during the reign of George III, except for individuals who continued to wear them as a symbols of their professions (e.g., judges, doctors, and clergymen). In fact, so many wigmakers were facing financial ruin that they marched through London in February 1765 to present George III with a petition for relief. Bystanders were infuriated, noticing that few of the wigmakers were wearing wigs although they wanted to protect their jobs by forcing others to wear them. A riot ensued, during which the wigmakers were forcibly shorn.

During the late eighteenth century, Louis XVI wore wigs to hide his baldness, and wigs were very fashionable throughout France. The modern technique of ventilating (attaching hairs to a net foundation) was invented in this environment. By 1784, springs were being sewn into French wigs to make them fit securely. In 1805, a Frenchman invented the flesh-colored hair net for use in wigmaking. A series of other improvements followed rapidly, including knotting techniques, fitting methods, and the use of silk net foundations. These matters were so important that a major lawsuit arose, and one inventor committed suicide after selling his patent cheaply and watching others become rich using his technique. One of the manufacturing processes that was tried at this time was based on the use of pig or sheep bladders to simulate bald heads on actors. In the mid 1800s, some wigs and toupees were made by implanting hairs in such bladders using an embroidery needle. In the late nineteenth century, children and apprentices of wigmakers amused themselves by playing the "wig game," in which each participant accumulated points by throwing an old wig up to touch the ceiling and catching it on the head as it fell.

Raw Materials

By the early 1900s, jute fibers were being used as imitation hair in theatrical wigs. Today, a favorite material for theatrical wigs, particularly those worn by clowns, is yak hair from Tibet. The hair of this ox species holds a set well, is easily dyed, and withstands food and shaving cream assaults.

Wigs of synthetic (e.g., acrylic, modacrylic, nylon, or polyester) hair are popular for several reasons. They are comparatively inexpensive (costing one-fifth to one-twentieth as much as a human hair wig). During the past decade, significant improvements in materials have made synthetic hair look and feel more like natural hair. In addition, synthetic wigs weigh noticeably less than human hair versions. They hold a style well—so well, in fact, that they can be difficult to restyle. On the other hand, synthetic fibers tend not to move as naturally as human hairs, and they tend to frizz from friction along collar lines. Synthetic hair is also sensitive to heat and can easily be damaged (e.g., from an open oven, a candle flame, or a cigarette glow).

Human hair remains a popular choice for wigs, particularly because it looks and feels natural. It is easily styled; unlike synthetic hair, it can be permed or colored. During periods of scarcity of cut human hair for wigs, manufacturers have used combings (hairs that fall out naturally at the end of their life cycle). However, actively growing hair that is cut for wigmaking is preferred. United States wigmakers import most of their hair. Italy is known as a prime source of hair with desirable characteristics; other colors and textures of hair are purchased in Spain, France, Germany, India, China, and Japan. Women contract with hair merchants to grow and sell their hair. After cutting, the hair is treated to strip the outer cuticle layer, making the hair more manageable. Wigmakers pay $80 or more per ounce for virgin hair, which has never been dyed or penned; a wig requires at least 4 oz (113.4 g) of hair.

Some manufacturers blend synthetic and human hair for wigs that have both the style-retaining qualities of synthetic hair and the natural movement of human hair. However, this can complicate maintenance, since the different types of hair require different kinds of care.

Types of Wigs

Ready-made wigs are available in stores and by mail order. They are one-size-fits-all models that adjust to individual heads by means of either a stretchy foundation or adjustable sections around the edge of the foundation. Ready-made wigs can be made of either synthetic or human hair and are available in either machine-made or hand-tied versions. Customers who are willing to pay more for a better fit can purchase semi-custom wigs that are hand-knotted on different sizes and shapes of stock foundations. The best fit, however, is achieved with a custom-made wig. Made to the customer's exact head measurements, these wigs are held in place by tension springs or adhesive strips, or can be clasped to existing growth hair. Silicone foundations can be molded to the exact head shape, so that they are held in place by a suction fit.

Machine-made wigs are fabricated by weaving hair into wefts (hair shafts that are woven together at one end into a long strip). These can be sewn in rows to a net foundation. When the hair is disturbed, by blowing wind for example, the foundation shows through the hair. Thus, such wigs are less desirable for people who have no growth hair under the wig. Hand-tied wigs, on the other hand, give a more natural look, particularly if slightly different shades of hair are blended before being applied to the foundation. Hand-tied wigs shed hair and must be repaired from time to time. With proper care, human-hair wigs generally last for two to six years.

The Manufacturing

Process

The following description reflects the making of a full, custom-fitted, hand-tied, human-hair wig. Such a wig would take four to eight weeks to make, and would sell for approximately $2,000 to $4,000.

Preparing the hair

- 1 The wigmaker must first make sure that the individual hairs are lying in the same direction. This is done by holding a small bunch of hair in the hand, and rubbing the ends between the finger and thumb. The tips (uncut ends) turn back during the rubbing, while the cut ends (which were closer to the hair's root) lie straight. If the hairs in the bunch are running in both directions, they must be turned by sorting the "root down" hairs into one pile and the "root up" hairs into another before recombining them into a single, organized bunch.

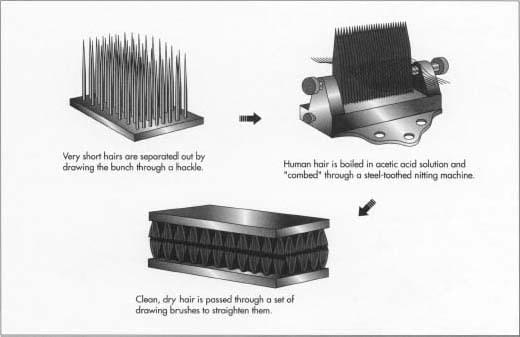

- 2 Very short hairs less than 3 in (7.5 cm) long are separated out by drawing the bunch through a hackle (wire brush) that is clamped to the workbench. After hackling, the usable hairs are tied together into bundles of convenient size. Fine string is used to tie the bundles tight enough to hold them securely, but loose enough to allow the string to be shifted while washing the hair.

- 3 The hair is carefully inspected for nits (louse eggs). If any are found, they are removed by boiling the hair in an acetic acid solution and combing it through a steel-toothed nitting machine.

- 4 Each bundle of hair is gently, but thoroughly, hand washed in a bowl of hot, soapy water that contains a disinfectant. The hair is then rinsed several times in clear water. The bundles are carefully squeezed in a towel and allowed to dry either in open air or in an oven set at 176°-212°F(80°-100°C).

- 5 Bundles of clean, dry hair are again hackled to straighten them. They are then passed through a set of drawing brushes, so the wigmaker can sort them into bunches of equal length, which are tied near the root end.

- 6 If desired, hair can now be permanently curled or waved. After the hair is wound onto curlers, it is boiled in water for 15 to 60 minutes (depending on the tightness desired) and then dried in a warm oven for 24 hours or more.

- 7 Heads of growing hair are not uniform in color. The wigmaker may prepare hair for a specific wig by blending as many as five or more slightly different shades of hair together to produce a more natural look.

Preparing the pattern

- 8 In order to get the best possible fit, the foundation of a custom wig is made as close as possible to the shape of the client's head. This can be accomplished either by measuring several aspects of the head directly, or by making a plaster cast of the head and using it as a model.

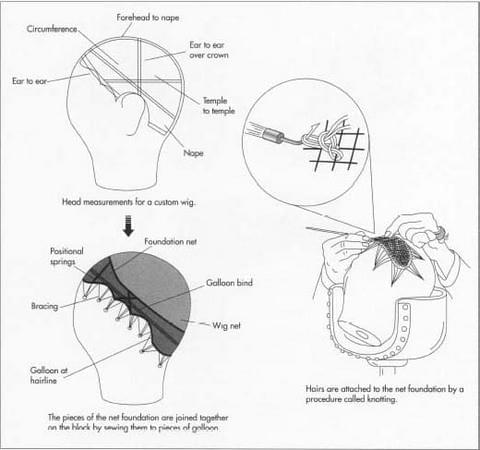

- 9 Six basic measurements are taken of the customer's head. The circumference is measured a half inch (1.27 cm) above the hairline at the nape of the neck, above each ear, and across the front of the head a half

- inch (1.27 cm) above the hairline. For adults, this measurement ranges from 19-24 in (48-61 cm). The second measurement is from the hairline at the front of the head to the hairline at the nape of the neck. The third is taken between points just in front of each ear, along the hairline at the front of the head. The fourth goes across the crown of the head, from just above one ear to just above the other. The fifth runs straight across the back of the head, from one temple to the other. Finally, the sixth measurement traces the nape of the neck.

In addition, the wigmaker must note such information as any unusual shape of the head, the length and location of any desired parting of the hair, and the desired style of the hair on the finished wig.

- 10 A pattern is drawn and cut from light-colored paper.

Making the foundation

- 11 The edge of the wig's foundation is cut from fine-mesh silk netting that matches the desired hair color. This piece varies in width from two or more inches (5 cm) in the front to one inch (2.5 cm) in the back. The crown of the foundation is cut from a coarser net made of silk, cotton, or nylon. If a part is to be incorporated in the wig, a strip of very fine, silk net (white or flesh-colored) is cut and inserted in the appropriate location on the foundation.

- 12 The paper pattern is carefully positioned on an appropriate size block (a wooden, head-shaped form). With this paper lying under the net foundation, the mesh of the net is easier to see and knotting is facilitated. The pieces of the net foundation are joined together on the block by sewing them to pieces of galloon (fine, strong silk ribbon that matches the color of the foundation netting). The foundation is held in place on the block by cotton thread sewn through the galloon and laced through anchoring points (steel loops hammered into the block).

- 13 Springs sewn into the foundation at strategic locations will hold the completed wig in place on the customer's head. These devices, 1.5-2 in (3.8-5.1 cm) long, are often made from steel watch springs or elastic bands and are encased in galloon.

Knotting

- 14 Hairs are attached to the net foundation by a procedure called knotting. Although various wigmakers use at least three types of knotting, the single, or "full V," knot is the most common. It is similar to the knot used in making a latch-hook rug. Using this knot, hairs 25 in (63.5 cm) long must be used to make a wig with 12 in (30.5 cm) long hair. Different sizes of ventilating needles can be used, depending on the number of hairs that are to be tied together in one knot. Along parts and the front edges of the wig, knots are usually made with single hairs, while in the crown up to eight hairs may be knotted together. A full wig requires 30,000 to 40,000 knots, which take a total of about 40 hours of tying.